“I don’t belong in the world; something separates me from other people”. After a car crash Mary, the protagonist in Herk Harvey’s “Carnival of Souls”, finds herself oscillating between life and death. At moments, she is fully part of her surroundings—she talks to her prying landlady, plays the organ in the church where she is employed, drinks coffee with her slimy boarding room neighbour. Then, all of a sudden, the scene ripples like water and Mary finds herself in a separate realm—she becomes invisible and inaudible to those around her. The rippling of water is a leitmotif throughout the film, from the opening credits to the lake from which the figure who embodies death emerges to capture Mary and take her back to where she never fully went after the car crash. This figure pops up throughout the film, following Mary, haunting her, fraying her nerves. She attempts to explain to people that the pale, shrivelled face is not a figment of her imagination. As cinematic formula dictates, they think her deluded, “hysterical”. Beneath their adamant denial, though, lies a nervous fear of the inexplicable.

*******

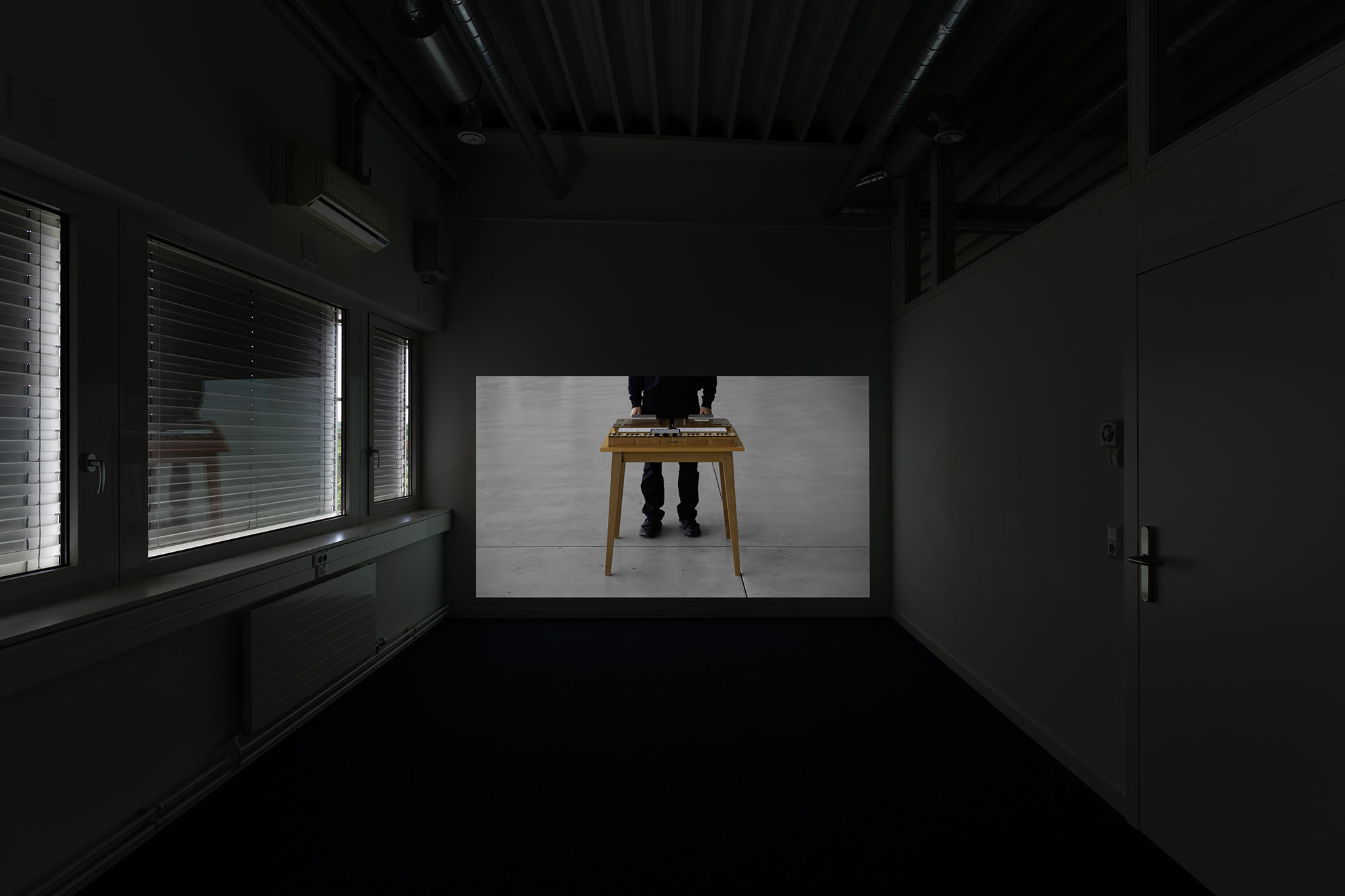

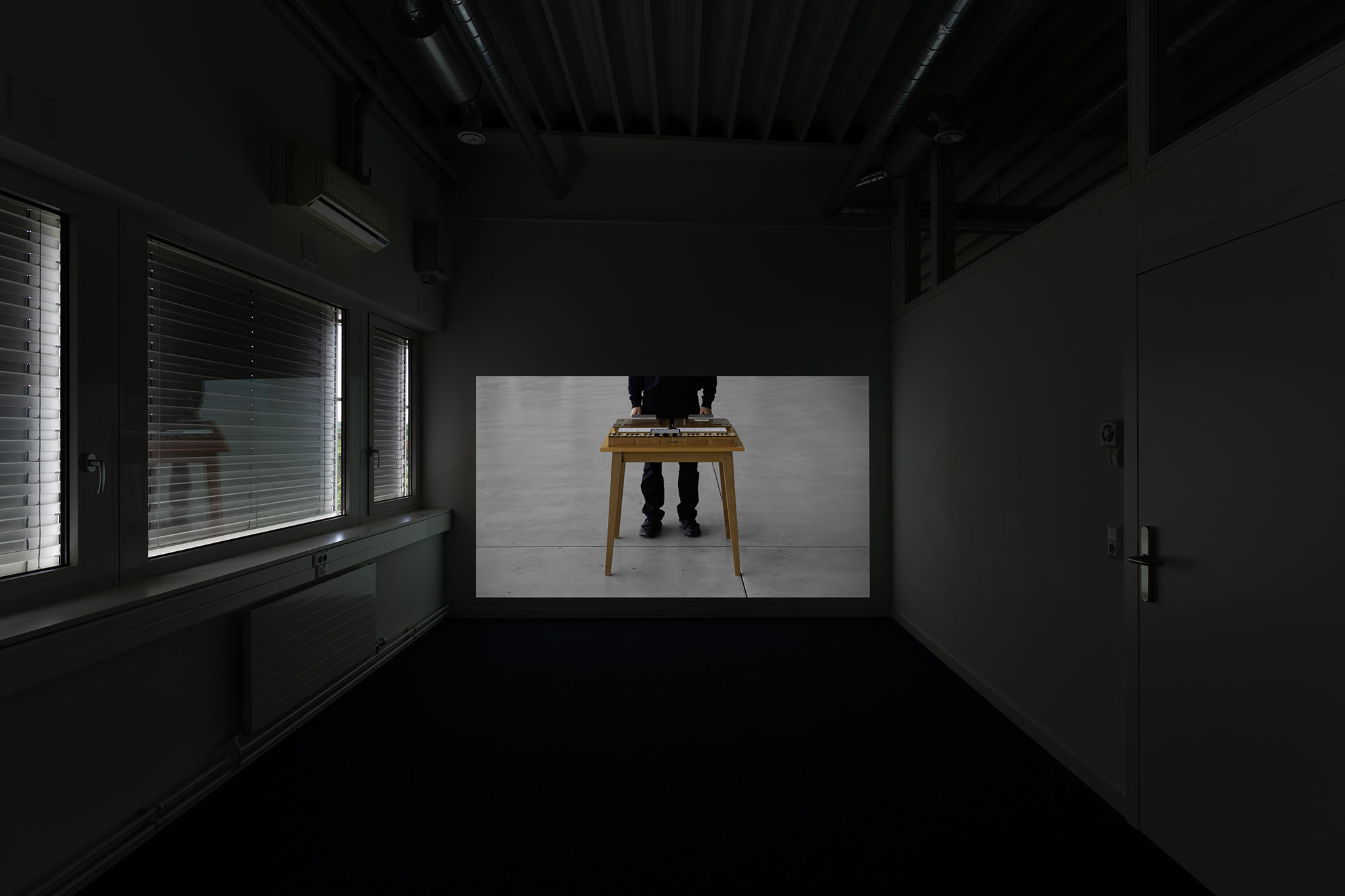

The importance of believing, or rather the suspension of disbelief, is at play when standing before Philip Seibel’s “Panels”. A series of actions—cutting, milling, sanding, painting, coating, assembling, gives the works their presence. But when I squint, these objects cease to be a mere accumulation of parts. They are, and always were, simply there. They emit a drone not unlike the organ music that comes out of Mary in “Carnival of Souls” as she plays, in a trance, an eerie, downtempo melody. A rational person, chastised by her tutor for the lack of sentimentality with which she approaches her job as a church organist, she now becomes a vessel for a deathly tune that manipulates her hands and feet as if she were a puppet.

*******

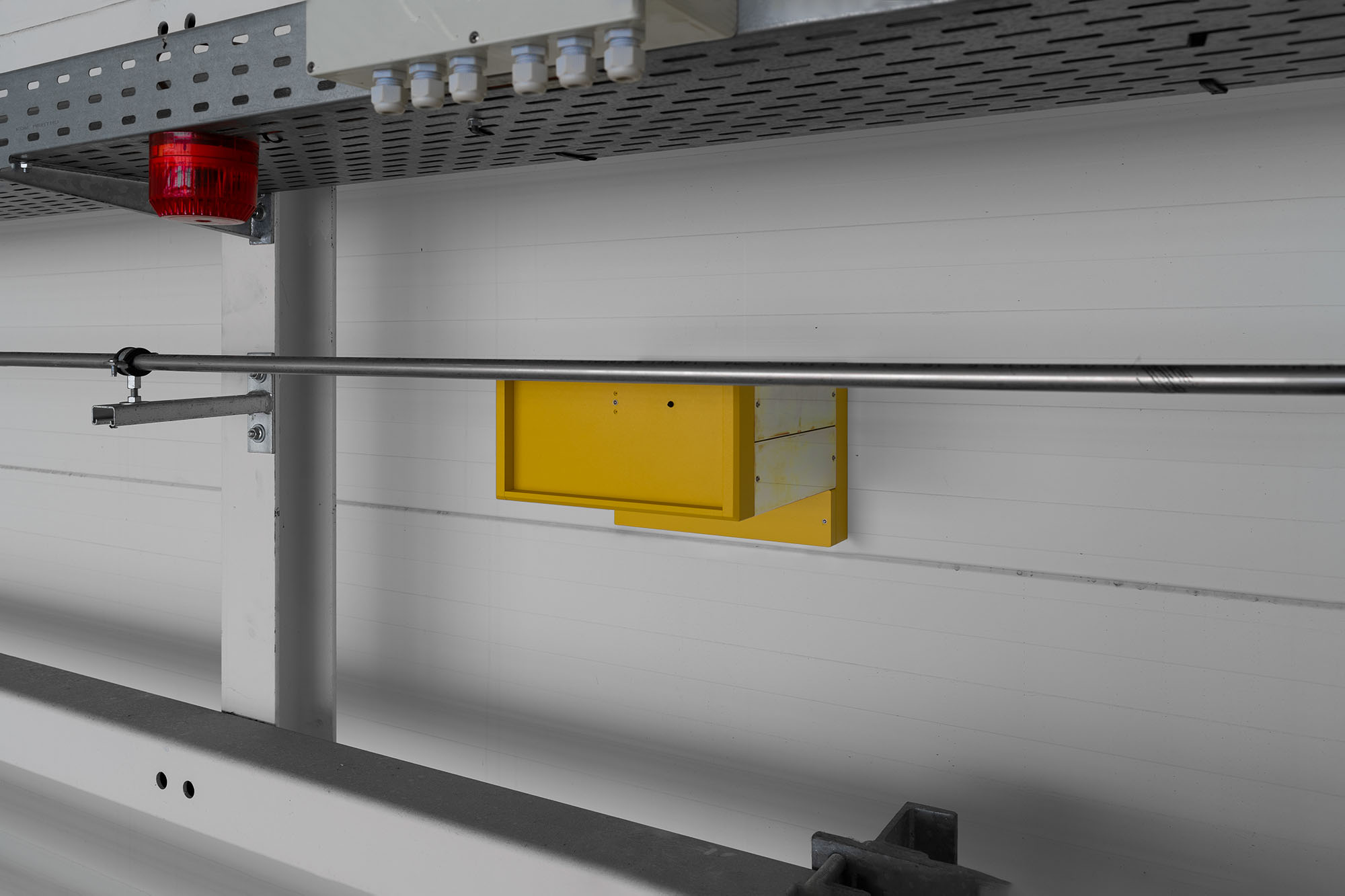

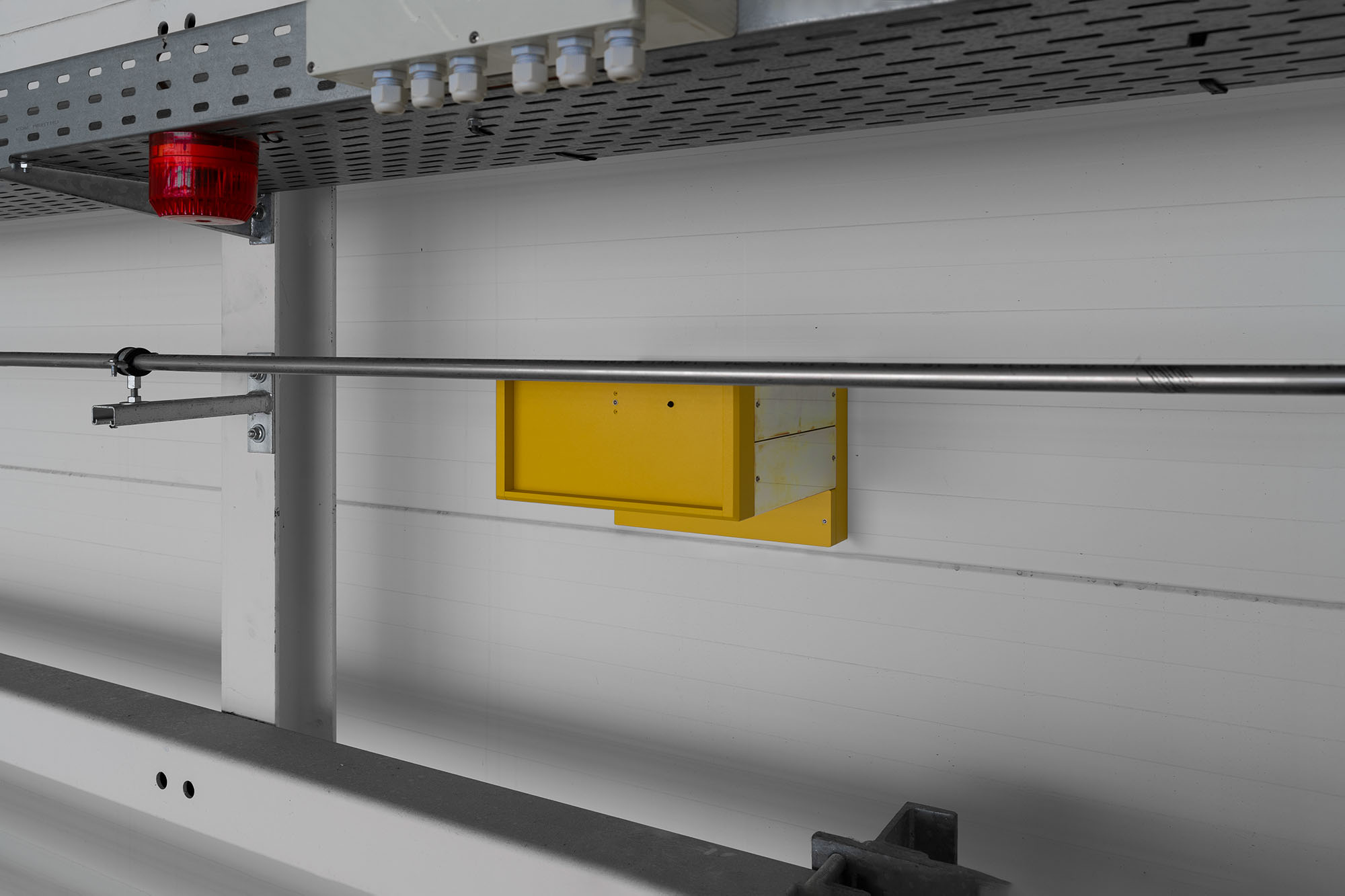

The word panel denotes a flat surface. Ultimately, this is what the works are: a series of surfaces masquerading as three-dimensional objects. Deceiving props that fool us with their façades, from strips of veneer that pass themselves off as solid wood, to the dizzying surface of crystallised paint, to the flat imperviousness of anodised aluminium. The sculptures in this exhibition are modified copies of an actual control panel, shown in Seibel’s exhibition “Warmth” at Lo Brutto Stahl in 2024. They are assembled from individual pieces that make up a body, a frame, and an inlay, the front of the panel that we are meant to interact with, to “control”. Subtraction and metamorphosis are as important in the making of the panels as addition is. The obviously wooden pattern of the veneers is hidden by layers of paint and lacquer, the properties and appearance of metal are altered through galvanisation and anodisation and wax reliefs are cropped and carved into.

The recasting of wax reliefs is a recurring procedure in Philip Seibel’s sculptures. The original reliefs, purchased on second-hand online platforms, depict both famous paintings and banal scenes in an inexpensive material. Little matter that they are cheap copies—they serve the same purpose as the originals, opening up a world which extends beyond their mere materiality. The act of recasting operates as a form of homage—to the infinite possibilities of wax as a material, which can be melted down and cast indefinitely, and to the notion of the copy and its apparent lack of subjectivity.

Imitation is at the heart of Seibel’s work, perhaps stemming from a hesitation to identify with what is often brushed aside as intuitive creation. But just as blind creation does not exist, neither can one speak of a conceptual act here. In the process of making the panels, a series of micro-decisions are made which do not necessarily have a rational reason behind them.

Something that is a conscious decision on Seibels’ part, and which manifests in all of his work, is a certain “holding back”. In making the wax copies, for example, he detaches himself from the direct symbolism of some of the scenes depicted in the original reliefs by modifying certain elements. A copy of Dürer’s “Knight, Death and the Devil” is turned on its side, evoking the possibility of multiple interpretations of the print. The two peasants from Millet’s “Angelus”—a symbolic scene that depicts a moment of intense calm in prayer amidst the drudgery of everyday farm life—have their heads lopped off. Other wax reliefs have been so heavily carved into that we can barely recognise what they depict anymore. The pathetic banality of traditional scenes and gendered situations has been rendered silent. The deeper grooves of these inlays call to mind set design from German expressionist cinema—jaggy and distorted, their tone so dark that our gaze sinks into them. It is the first time that the wax reliefs have been so overtly carved into by Seibel, and they are also the only element in the exhibition that lets the artist’s hand transpire. Yet far from being at odds with the other elements that make up the panels, which are so flat and sterile as to make us believe that they have been industrially produced, they originate from the same desire to be unobtrusive and follow a logic of revelation through concealment.

*******

Once fully assembled, the panels are removed from the layers of actions that make them what they are. A cacophony of different materials and finishes fuses into an object that buzzes and hums with a presence that is at once deadly silent, yet so tangible that I can almost communicate with them. Curious as to what they contain, how they are made, how they came to be, we glimpse through the small holes in their surface. Their interior remains inaccessible, but contained within these seemingly impenetrable vessels is a glimmer of blind faith in that which we cannot rationalise away.

— Marta Riniker-Radich